2 Introduction – integrated management of an intensively used sea area

2.1 A living sea

The North Sea–Skagerrak area is Norway’s most intensively used sea area, an engine of the Norwegian economy and a source of growth and prosperity. These are some of the most heavily trafficked waters in the world, with a large volume of shipping and considerable fisheries activity. The area is also important for local commercial activities and tourism along the coast. The North Sea is Norway’s largest petroleum province and suitable for the development of wind power. Access to the sea and opportunities to stay by the seaside and enjoy activities such as boating, swimming and fishing are important for a large proportion of the population, and form a basis for the tourist industry. And opportunities to enjoy the seaside are strongly dependent on a clean, rich and productive marine environment – a living sea means a living coast.

The state of the North Sea and Skagerrak environment used to be considerably poorer than it is today. For many years the sea was used as a refuse dump, and industrial waste water and domestic sewage were discharged untreated. For a long time, people acted as though the oceans could absorb anything that was dumped into them. Recently, however, binding cooperation in various international forums and between the eight North Sea countries has resulted in major improvements. Cooperation in the North Sea–Skagerrak area demonstrates how fruitful international environmental cooperation can be, and how targeted efforts can yield results. This cooperation has also produced a considerable body of knowledge about the North Sea and Skagerrak.

Nevertheless, the state of the environment in this area still gives cause for concern and is unsatisfactory in many ways. Concentrations of hazardous substances are higher in the North Sea and Skagerrak than in Norway’s other sea areas, and quantities of marine litter are higher than anywhere else in the Northeast Atlantic. Much of the pollution originates elsewhere. In addition, the state of certain fish stocks gives cause for concern, and a number of seabird species are threatened. Climate change and ocean acidification will give rise to new management challenges, and a long-term approach will be required. This situation makes it necessary to improve environmental status and ecosystem resilience, and to strengthen the basis for continued value creation through use and harvesting of the area.

2.2 Purpose, roles and work process

The Government’s goal is for Norway to be a pioneer in developing an integrated, ecosystem-based management regime for marine areas. The Government will therefore continue to use the system of management plans for sea areas.

The purpose of this management plan is to provide a framework for the sustainable use of natural resources and ecosystem services derived from the North Sea and Skagerrak and at the same time maintain the structure, functioning, productivity and diversity of the area’s ecosystems. The management plan is thus a tool for both facilitating value creation and maintaining the environmental values of the sea area.

With the publication of this management plan, the Government has established integrated, ecosystem-based management plans covering all Norwegian sea areas. The other plans are for the Barents Sea–Lofoten area (Report No. 8 (2005–2006) to the Storting, updated in 2011 in Meld. St. 10 (2010–2011)), and the Norwegian Sea (Report No. 37 (2008–2009) to the Storting).

The management plans are intended to promote integrated, ecosystem-based management of Norwegian sea areas. They clarify the overall framework and encourage closer coordination and clear management priorities. They increase predictability and facilitate coexistence between industries that are based on the use of these sea areas and their natural resources. The management plans are also intended to be instrumental in ensuring that business interests, local, regional and central authorities, environmental organisations and other interest groups all have a common understanding of the goals for the management of the area in question. The Government will continue and further develop the system of management plans, and make it more effective.

The Ministry of the Environment is responsible for ensuring coherence in environmental policy, and is therefore responsible for heading and coordinating work on the management plans. However, a key feature of the management plan system is that all relevant authorities play an important part in developing the plans.

Work process

Work on this management plan was organised along the same lines as for previous management plans. It was coordinated by an interministerial Steering Committee including all the relevant ministries and headed by the Ministry of the Environment. An important feature of the management plan system is that relevant subordinate agencies and key research institutions cooperate in drawing up the scientific basis for the plans. The relevant agencies may vary to some extent between sea areas. The scientific basis for the North Sea–Skagerrak management plan was prepared by an Expert Group headed by the Climate and Pollution Agency and including representatives of the Directorate for Nature Management, the Directorate of Fisheries, the Institute of Marine Research, the Coastal Administration, the National Institute of Nutrition and Seafood Research, the Norwegian Institute for Air Research, the Norwegian Institute for Nature Research, the Norwegian Institute for Water Research, the Norwegian Water Resources and Energy Directorate, the Petroleum Directorate, the Petroleum Safety Authority Norway, the Maritime Directorate and the Norwegian Radiation Protection Authority. Two advisory groups for the management plans, the Advisory Group on Monitoring (headed by the Institute of Marine Research), and the Forum on Environmental Risk Management (headed by the Norwegian Coastal Administration) have also been involved.

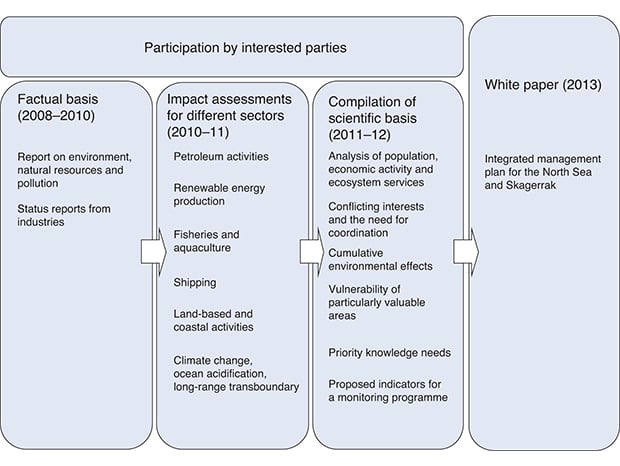

Figure 2.1 Stages in the preparation of the North Sea–Skagerrak management plan.

Source Ministry of the Environment

A scientific basis was compiled for the white paper, and includes topics such as biodiversity, pressures and impacts, and human activity. Chapters 3–7 describe the knowledge base, in line with the knowledge requirements of Norwegian legislation such as the Nature Diversity Act and the Marine Resources Act. Chapter 3 describes the state of the environment in the management plan area. Chapter 7 describes and assesses the cumulative environmental effects on the ecosystems of the area. This approach is in accordance with the requirement to assess cumulative environmental effects and apply the precautionary principle, as set out in the Nature Diversity Act.

In preparing the North Sea–Skagerrak management plan, economic considerations have been given more emphasis than in earlier management plans. This approach will be further developed in future updates of all the management plans.

Now that management plans have been drawn up for all Norwegian sea areas, the Government will take steps to simplify the way the work is organised and make updating the plans more effective.

The relevant sectoral authorities have the main responsibility for implementing the measures set out in the management plans under the legislation they administer, for example the Marine Resources Act and the Act relating to ports and navigable waters (Ministry of Fisheries and Coastal Affairs), the Petroleum Activities Act (Ministry of Petroleum and Energy and Ministry of Labour), the Offshore Energy Act (Ministry of Petroleum and Energy), the Maritime Safety Act (Ministry of Trade and Industry and Ministry of the Environment), and the Pollution Control Act and Nature Diversity Act (Ministry of the Environment).

Consultation

Participation by interested parties is also an important element of the management plan work. The Expert Group has ensured participation in the work on the scientific basis through consultation on the background reports and consultative meetings during the process of developing the plan. After the Expert Group had delivered the scientific basis to the ministries in May 2012, a conference was held in Haugesund on 22 May to give all interested parties an opportunity to discuss the reports. After the conference, interested parties were also invited to provide written input. The responses of the various parties made an important contribution to the preparation of this white paper, and are all available on the website of the Ministry of the Environment.

2.3 The management plan area

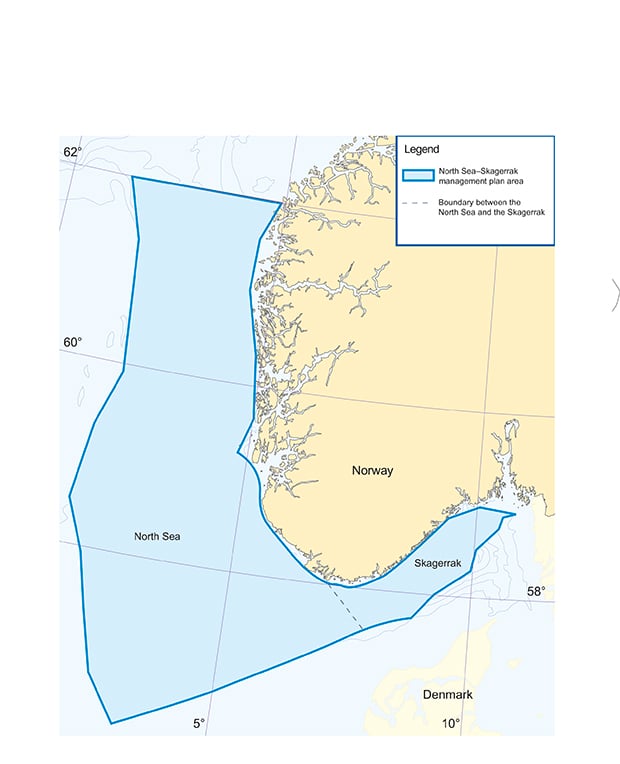

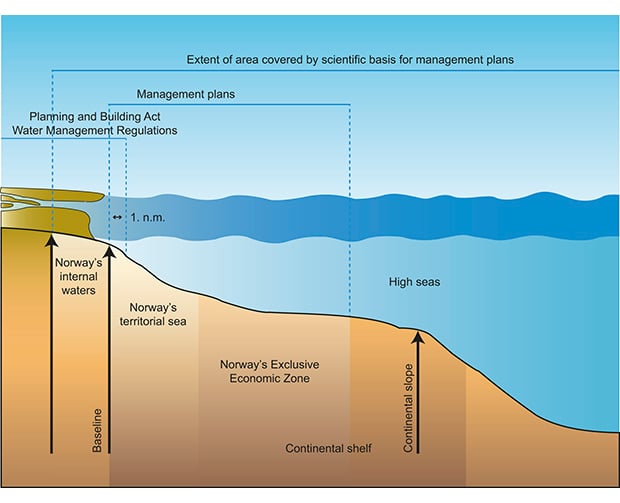

The area covered by the scientific basis for the management plan comprises the entire North Sea and Skagerrak, including waters along the coast and areas under the jurisdiction of other countries. The actual management plan and the measures described in it apply primarily to the open sea in the Norwegian part of the North Sea and Skagerrak, i.e. the areas outside the baseline, in Norway’s territorial waters and exclusive economic zone northwards to latitude 62 °N (off the Stad peninsula). The management plan does not cover areas within the geographical scope of the Planning and Building Act or the Water Management Regulations, with the exception of an overlap in the area from the baseline to one nautical mile outside the baseline. This means that the management plan does not determine the framework for activities in the coastal zone, such as fish farming. Environmental pressures from land-based and coastal activities are therefore categorised as external pressures in the management plan.

Figure 2.2 The North Sea and Skagerrak management plan area

Source Norwegian Mapping Authority

2.4 Management plans in an international context

Norway’s management plan work has put the country at the forefront of efforts to develop an integrated ecosystem- based management regime. Coastal states have a clear duty under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea to protect the marine environment. This is bound up with the extensive rights coastal states have under the Convention to utilise living marine resources and other resources on the continental shelf under their jurisdiction.

Figure 2.3 Geographical scope of Norway’s management plans, the Planning and Building Act and the Water Management Regulations.

Source Adapted from OSPAR QSR 2010

Under the Convention on the Law of the Sea, countries also have a duty to cooperate at regional and global level to protect and preserve the marine environment. In the 1980s and 1990s, international cooperation on the marine environment focused largely on reducing the worsening pollution of the seas. Through the regional Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the North-East Atlantic (the OSPAR Convention) and its predecessors (the 1972 Oslo Convention and the 1974 Paris Convention), and the North Sea Conventions (1984–2006), specific obligations were adopted that have led to a considerable improvement in pollution levels, particularly in the North Sea–Skagerrak area. Together with the other Nordic countries, Norway was a driving force in this work (see Box 2.1).

Textbox 2.1 The North Sea and Skagerrak – an international sea area

The North Sea and Skagerrak are strongly influenced by human activity. About 160 million people live in the catchment area, and all eight countries surrounding the sea area – Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, France and the UK – must cooperate to ensure an effective joint management system.

Parts of the North Sea were suffering from eutrophication and pollution as early as the 1800s, as a result of growing sewage discharges, runoff from agriculture and emissions from an expanding industrial sector. Between the mid-1800s and the 1960s, all the North Sea countries gradually introduced national legislation to combat pollution and by the late 1960s, it had become obvious that the North Sea countries also needed to agree on joint management of the North Sea and Skagerrak. The Torrey Canyon disaster was particularly important in triggering the political will to agree on binding joint rules. A few years later, the Stella Maris incident gave further momentum to the process of putting in place binding international agreements.

The Torrey Canyon was a Liberia-registered supertanker that was carrying a huge cargo of crude oil when it ran aground off the coast of Cornwall in south-western England in 1967. The oil spill from the wreck caused serious damage along both the English and the French coastlines, and clean-up operations required joint action by the British and French authorities. The accident triggered international action: at global level by the International Maritime Organization (IMO), which adopted the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL 73/78), and at regional level through the negotiation of the Bonn Agreement (Agreement for Cooperation in dealing with Pollution of the North Sea by Oil and Other Harmful Substances).

The Dutch ship Stella Maris sailed from Rotterdam in 1971 to dump chemical waste at sea, but was prevented by local protests and strong pressure from the countries near the proposed dumping sites (the first plan was to dump the waste near the Norwegian coast, then between Iceland and Ireland). In the end, the ship returned to port and the Netherlands finally had to dispose of the waste on land. This incident speeded up the adoption of the 1972 Oslo Convention or the Prevention of Marine Pollution by Dumping from Ships and Aircraft, in which the Norwegian authorities played a leading role. The London Convention on dumping at sea, a global convention based on the same criteria as the Oslo Convention, was also adopted in 1972.

The new willingness to take joint action in the North-East Atlantic region also resulted in growing awareness of the harmful inputs of nutrients and other pollutants from land, and to the adoption of the Paris Convention for the Prevention of Marine Pollution from Land-Based Sources in 1974. The Oslo and Paris Conventions set up a joint secretariat in London, and were merged into one convention, the Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the North-East Atlantic (still known as the OSPAR Convention), in 1992.

The series of North Sea Conferences held between 1984 and 2006 were another expression of the willingness to cooperate and understanding of the need to do so. These high-level political meeting places provided an opportunity to discuss all pressures on the North Sea – pollution, fisheries, oil and gas activities, and shipping – from an overall perspective. The North Sea countries adopted joint declarations with ambitious goals, for example to halt dumping of waste from ships and reduce inputs of nutrients and hazardous substances. These goals have also had a strong influence on developments within the OSPAR cooperation and the EU, where the political goals have been translated into more legally binding rules. After the North Sea Conference on shipping and fisheries in Gothenburg in 2006, it was decided to continue the work within the framework of relevant conventions and organisations (OSPAR, NEAFC and IMO) and through active cooperation between these forums.

Since the adoption of the Oslo and Paris Conventions in the early 1970s, the oil and gas industry in the North Sea has expanded greatly. The 1992 OSPAR Convention therefore included a separate annex regulating pollution from offshore sources. In 1995, it emerged that the British authorities were planning to permit dumping of the Brent Spar, a disused oil storage buoy, in the North Sea. This caused political controversy at the North Sea Conference in Esbjerg in the same year. Brent Spar was finally towed to Norway (Erfjord in Rogaland), where it was decommissioned and the materials were re-used in new port facilities being built just outside Stavanger. The case sparked much political discussion between the North Sea countries. At the first ministerial meeting under the OSPAR Convention in 1998, rules on the disposal of disused offshore installations were adopted. They state that disused offshore installations must as a general rule be removed, but that exceptions may be made on specific conditions and after consultation with the other parties involved, for example for concrete installations. At the same ministerial meeting, a new annex to the OSPAR Convention on the protection of marine biodiversity was adopted. Using this as a basis, OSPAR has in recent years made its mark both globally and regionally through successful cooperation on the protection of marine areas, species and habitats.

Within OSPAR, the main focus has now shifted from traditional pollution issues to the need to maintain species and marine biodiversity. The Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) is the most important global cooperation forum in this field. A target has been adopted under the Convention that by 2020, 10 % of coastal and marine areas, especially areas of particular importance for biodiversity and ecosystem services, will be conserved through effectively and equitably managed, ecologically representative and well connected systems of protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures, and integrated into wider seascapes. A major effort is now underway within the framework of the Convention to collect information on ecologically or biologically important marine areas. In cooperation with the North East Atlantic Fisheries Commission (NEAFC), OSPAR has initiated work to identify such areas, mainly in international waters in the North-East Atlantic, with a view to presenting proposals to the Conference of the Parties to the CBD in 2014.

Norway’s management plans are policy instruments. They take a long-term approach to the protection of marine ecosystems, and are therefore a key tool for meeting Norway’s obligation under international law to protect the marine environment of its seas. They are also flexible; the regular updates allow for changes to earlier decisions within their overall framework, on the basis of new and updated information. This means that in addition to protecting ecosystems, the plans also provide for Norway to make use of its right and duty under international law to make sustainable use of the resources in its sea areas.

To achieve good environmental status in its sea areas, Norway is dependent on other countries taking steps to protect the environment and manage their resources sustainably. It is clearly in Norway’s interests for the other North Sea countries to meet their commitments. In 2008, the EU adopted the Marine Strategy Framework Directive, with the aim of achieving good environmental status in all European marine waters by 2020. To this end, each member state is to develop a marine strategy for its waters. These will include the establishment of environmental targets, indicators, monitoring programmes and programmes of measures. In other words, the directive sets out much the same approach and the same methods as Norway’s integrated management plans. However, the Government has found that the directive is not EEA-relevant, and Norway is therefore not bound by its provisions.

Textbox 2.2 Marine protected areas and OSPAR

The parties to the OSPAR Convention have been working together for a number of years to establish a network of marine protected areas (MPAs). Until 2010, the network consisted of areas within the parties’ national jurisdiction. These were protected in different ways under national legislation and nominated as components of the network. At OSPAR’s ministerial meeting in Bergen in 2010, it was decided to establish six MPAs in areas beyond national jurisdiction. The network now consists of more than 280 MPAs in areas within and beyond the parties’ national jurisdiction.

The ongoing work of identifying areas of the North-East Atlantic that may be ecologically or biologically valuable will provide an important basis for continued joint efforts to establish more MPAs.

OSPAR does not adopt measures targeting fisheries or shipping, and active cooperation with NEAFC and IMO is therefore essential for effective management of MPAs in areas beyond national jurisdiction. As early as 2009, NEAFC had closed several areas beyond national jurisdiction to bottom fishing to prevent damage, and these overlap extensively with the OSPAR MPAs in areas beyond national jurisdiction. Studies are also being carried out within OSPAR on pressures and impacts from shipping in the MPAs as a basis for possible protective measures in cooperation with IMO.

Another joint initiative has therefore been taken to develop a collective arrangement involving OSPAR, NEAFC, IMO and the International Seabed Authority regarding principles for the management of areas beyond national jurisdiction that have been given some form of protection. Examples of such protection include OSPAR MPAs in areas beyond national jurisdiction and NEAFC’s closures of areas beyond national jurisdiction to bottom fishing, and any future steps by IMO and the Seabed Authority. This cooperation model is important and is arousing considerable international interest, for example in connection with the UN’s discussions on conservation and sustainable use of marine biodiversity in areas beyond national jurisdiction in the context of the law of the sea. Norway is working actively to gain international acceptance of this form of cooperation.

The Norwegian environmental authorities have entered into cooperation with Sweden and Denmark to ensure scientific coordination of the management of adjacent areas under their jurisdiction in the North Sea and Skagerrak. The OSPAR framework provides a basis for establishing similar cooperation with the other North Sea countries. It is important to continue developing the management plans so that Norway can continue to be at the forefront of developments and maintain its legitimacy and influence as a driving force in international efforts, especially as regards the North Sea and Skagerrak.